Why Does My Cash Not Match My Income Statement?

In the prior post on forecasting cash flow, we addressed the inherent challenges with budgeting, namely that it only addresses the income side of the business while neglecting the cash flow. We established that the major challenge to managing a business is not predicting taxable income, but rather predicting and determining cash flow.

If you have created a forecasted cash flow from your income statement, you may have arrived at the conclusion that your timing was off on your purchases. You may also see, even after updating for actual expenses, the cash balances don’t match your spreadsheet.

Actual cash flow is more complex than your income statement.

You just came to this exact conclusion.

To effectively track your cash you will need to separate out the most common variances.

Here are the most common discrepancies between your income statement and your cash flow and how you can manage them.

1. Debt Payments

Operating Loans vs. Term Debt

For the purposes of the cash forecast there are two types of debt payments to track: term debt and operating lines. Term debt is your ordinary car loans or real estate loans; a loan with (hopefully) a fixed rate and specified repayment term. Be it three, five, ten, or even thirty years, you know your monthly requirement.

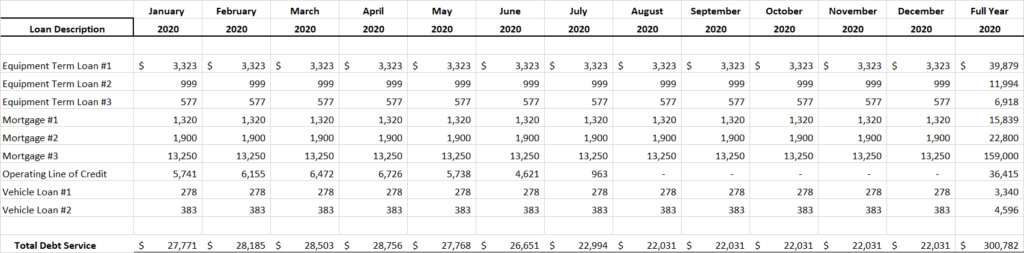

If you have multiple loans you will want to create a separate spreadsheet for your debt payments arranged in the same way as your monthly cash flow forecast. These should be subtotaled for the month to track your required payments.

In contrast to term debt, operating loan balances (or lines of credit) fluctuate. If you’re purchasing inventory with your line, your balance increases and your required payment is generally only the interest on the loan. An increase in your balance leads to a higher interest payment and lower cash flow.

Operating loans are inherently more challenging to calculate for the purposes of this exercise because you only need to calculate the interest to be repaid. Since the operating loan is used to spend immediately, it is easiest just to track the difference in the balance from month to month. (The purchases and interest expense will show up on your income statement and be counted for your cash forecast.)

This is an example of how your debt repayment page can look. Notice the operating line repayment does not stay constant. In this example, the line increases quickly at the beginning of the year but is paid off by August.

Track debt repayments separately because they include principal repayment, a required cash outflow not deductible on your tax return.

2. Capital Investments

Financial reporting and the IRS require accountants to move purchases of assets above a certain threshold or expected life from an expense to an asset. This process is known as “capitalizing” a purchase, turning a purchase from an expense to a capital asset.

Capital investments is a broad term encompassing a large variety of purchases. In fact, you may not even realize your purchase is a capital purchase until after your accountant reclassifies it.

As a refresher, an expense shows up on your income statement as a subtraction from income. An asset, however, goes directly to your balance sheet and is only deducted from your income when it is depreciated. By nature, the outflow of cash from a capital purchase won’t match your income statement. The cash outflow only shows up as an increase in assets on your balance sheet.

You may not know (or care?) about this but it does impact your forecasting of your cash. Capital investments need their own separate line on your forecast. This line will include only the cash you put into the purchase.

You may not know (or care?) about this but it does impact your forecasting of your cash. Capital investments need their own separate line on your forecast. This line will include only the cash you put into the purchase.

Purchasing with 100% cash? Just write down the cost on your “Capital Investment” cash outflow line.

If you are taking out new debt for a purchase, only include the cash down payment you made on the loan. (The loan will be included on the debt sheet.)

3. Distributions

Now for a fun line, distributions. I’m using the term distribution regardless of the filing status of your business. Whether you call it a dividend, distribution, shareholder loan or an owner draw the mechanics of this cash “expense” remain the same.

As an owner of the business, you split the role of employee with the role of owner. One is for the service performed for the business and one is a return on your investment in the business. If you’ve read about reasonable compensation, you know this is a gray area and the IRS likes to challenge your payroll if it is “unreasonable”.

As an owner, removing cash from your business is not deductible. It is not an expense because this cash outflow does not impact the income statement. It does impact your cash.

Many small business owners divide the total amount of money they will remove from their business using a ratio. The part they remove via a paycheck is expensed in the business but the part they remove as a distribution is not. To the owner, s/he receives the same cash but the distribution won’t show on the income statement.

To balance your cash outflow, it is crucial to add a line to your cash outflow for distributions to the owner. While these payments may not impact your taxable income, they will impact your cash.

Reconcile Your Cash Forecast to Actual Monthly

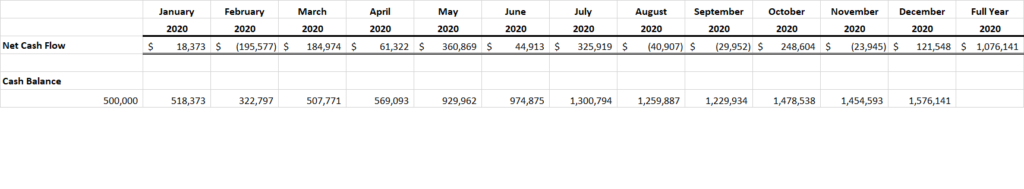

The purpose of your cash forecast is to tell you the balance of your cash at a given date. One difference between your income statement and cash forecast is your cash forecast needs to have a line showing the expected balance of your cash.

A forecast that does not show a cash balance would be useless, as that is its primary purpose. To track the cash balance add the 12-31 cash balance before the January column on your forecast. Then add the “Net Cash Flow” generated by your business to the balance as of 12-31 to arrive at your ending January balance. It could look like this:

This allows you to see the impact to your business of possible changes or investments you make. If the cash flow dips below $0 at any point, you may want to use someone else’s money (financing) to smooth out your cash flow.

After you have created your cash forecast, spend time each month reconciling it. This will give you much greater insight into your business than just relying on your traditional financial statements. It will also allow you to speak the language of a banker or purchaser.

Focus On Cash

There are other items impacting cash but debt payments, capital assets, and distributions are three of the largest variances between income and cash. Identifying the cash outlays on these categories will help you understand where your cash is going every month. Understanding your cash flow is critical to the success of your company.

This is merely one way to track cash. Do you have another way? Email me to tell me how you track your future cash flow.