How Do I Best Use Classes in QBO?

The chart of accounts (CoA) for MSPs can get unruly quickly. Consider a leader in the industry uses a CoA template that includes over 150+ rows. The sheer size and complexity of the amount of information leaves users overwhelmed, craving simplicity and utility.

There is a limit to the usefulness in the length of a CoA. As described here, adding rows of information and new accounts does not necessarily provide you with better or more effective reporting. In some software, you are penalized for adding more accounts to your CoA (see #8). Using classes in QuickBooks is a more effective way to dissect your business to understand it more clearly.

Most businesses use their income statement as their primary reporting function. Adding a new income or expense account or subaccount adds to the length of the income statement.

One of the ways you can be sure people won’t read or understand your income statement is to make it long with many accounts and subaccounts.

It may not matter to you at this point in your business, but if you have any future financing goals, plan to add any partners, or have any intention of selling your company, you want to make your business easy to explain and understand.

The income statement is structured based on your CoA and it will reflect changes made to your CoA. Adding an account to your CoA will increase the length of your income statement. This is a vertical addition. In terms of a spreadsheet, this is the equivalent of adding a row.

Instead of adding an additional row, using classes in QuickBooks essentially adds a “column” to the “spreadsheet” of information. This avoids overwhelming the user with a three-page income statement.

Classes can be user-defined for your business but you will want to use them sparingly.

Classes are often referred to as business units or departments in other software and correspond to groups in ConnectWise. These are segments of your business roughly performing the same task with P&L functionality for each class. The purpose of using classes is to compare each class against each other in a usable format.

To be most useful, each class should utilize the same accounts in the CoA. The classes should not have their own unique accounts within the CoA.

For example, if your business has multiple managers responsible for separate locations, you could create a class for each location of the business to compare the profitability of each location. (Please note, this is not the same as tracking by location in QuickBooks.)

Each class uses the same CoA so it can be compared side by side for reporting purposes. The information is granularly reported and allows for quick comparison.

An effective class is a finite group that uses the same accounts in the CoA.

Dissecting your financial statements by class segments the income statement into smaller, more understandable units. In selecting classes, there are many options to choose but you will need to determine what is the most helpful for you and your stakeholders. If you choose to track your business using classes, you are starting a new chapter and will add to the complexity and accounting for each transaction.

Some of the more common examples include:

- Location

- Business/service line

- Consultant/partner

- Client

- Specialization

- Product line

Classes may be helpful if you meet the following criteria:

- You can segment your business to compare results by business units engaged in a similar business.

- Each income and expense is easily assigned to a business unit.

- There are a finite number of classes to track.

- There is minimal overhead (expenses to allocate among all the other business units).

- If there are overhead expenses, the allocation percentages are easily understandable and repeatable.

- Most employees fit neatly into one class. Employees are assigned to one class and are not shared resources. If they are shared, they are split with even percentages. Employees aren’t shared between three or more classes and the sharing percentages are not custom for each employee.

- Your accountant has documented the policy, understands how to use classes, and is diligent to apply them to all transactions.

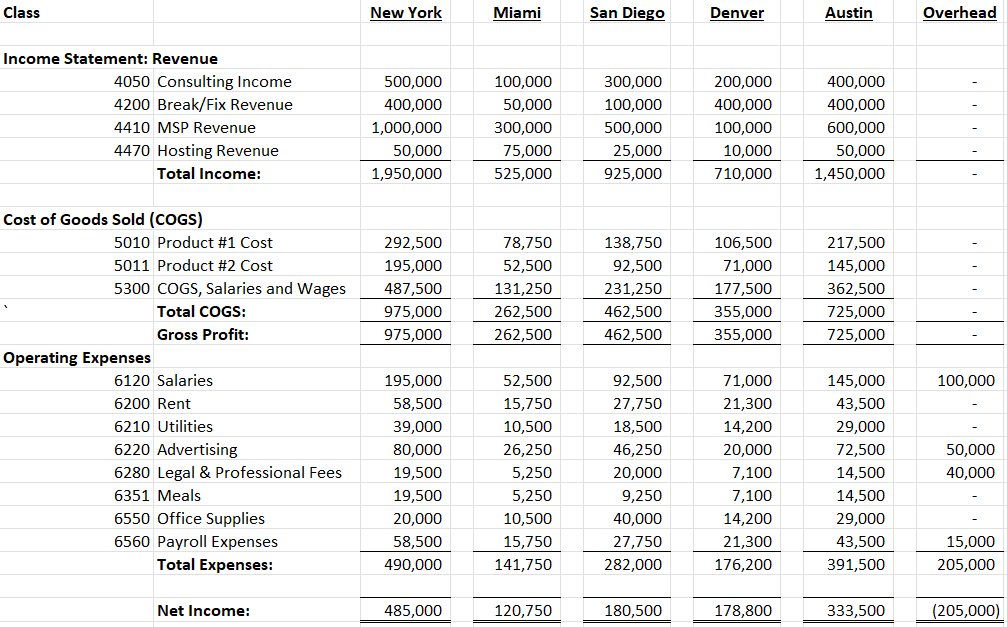

Assuming all these conditions are met, you can have an excellent income statement by class. Below is an example of what that can look like.

Example 1: Clear distinction of profit by location

In this example, the income and expenses for the business are divided into classes based on location. All locations are represented here and all revenue and expenses are included in one of these classes.

Furthermore, each location has the same product mix and expenses. There are some overhead expenses for salaries and other expenses and those will be allocated among the various five offices to close out the financial statements (according to policy). The business can access this report by running a ‘Profit and Loss by Class’ report.

Classes will not be helpful if you meet the following criteria:

- The list of potential classes is unlimited. They are dependent on unending future events. You always sell a product in a group and a new group constantly needs to be created. In this situation, it is better to manage this through the accounts.

- The product, cost of sales and expense accounts are not shared by the potential classes.

- Most expenses are allocated to overhead.

- You have no method of segmenting your inventory/cost of sales. You purchase inventory centrally with no clear allocation of how much was sent to a given class.

- You don’t like creating financial policies or you change them frequently thereby eliminating the usefulness of the comparisons.

- Each class uses different wage or expense codes.

- Your accountant is inconsistent in assigning classes. The ‘Profit and Loss by Class’ report shows expenses in the “Not Specified” or “Unclassified” column.

- Each employee has a custom allocation breakdown.

Below are two examples of income statements tracked by class with their weaknesses.

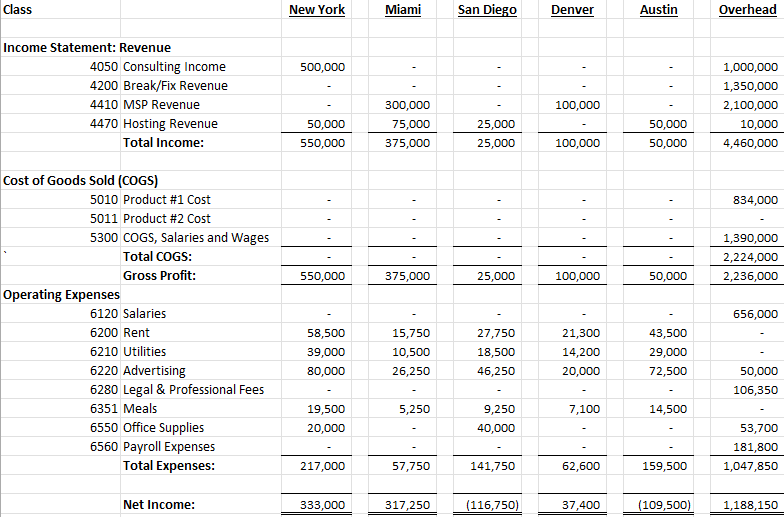

Example 2: Too much overhead

In this example, the locations are the same as in example 1 but a significant amount of revenue, COGS and expenses are not allocated among the locations. All forms of salaries & wages and the associated payroll costs are not allocated to the location. While the payroll can be properly set up to allocate these costs directly, there is more manual work to be completed for this. The income statement creates more questions than it answers.

Where was the revenue generated?

Is there a central location not listed?

Why does the business maintain two offices if they are losing money?

Presumably, this company will use its month-end procedures to allocate the overhead among the various classes according to policy. While technically correct, this much overhead indicates guessing at the overhead amounts. The results of that predetermined allocation will provide too much variability in the data rendering it useless.

This reporting is incomplete because it does not provide clarity about the business.

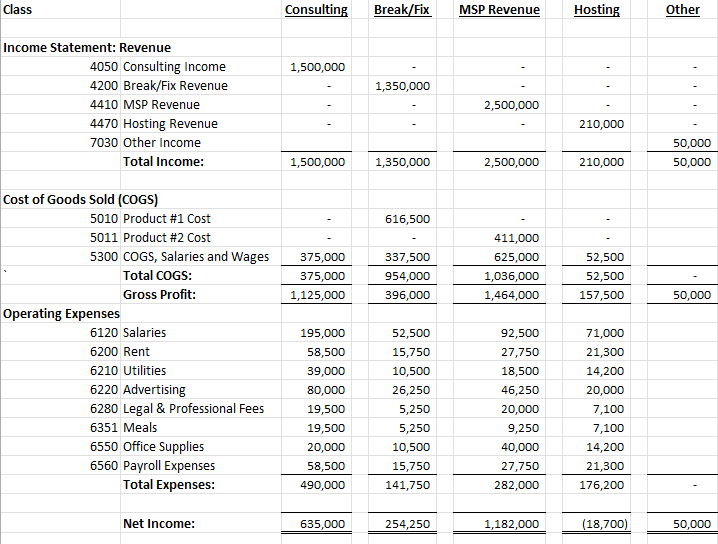

Example 3: Using the account codes as classes

While at first glance this income statement appears to segment the business, the reality is the accountant is working extra for the same information that could be gained using only the account codes. Using the account codes as classes is ineffective because each class is not utilizing the CoA. The classes are not able to be compared. If the revenue and cost of sales are assigned to their proper account, the financial statements’ user can easily see profitability without the extra hassle of using classes.

Classes can bring greater clarity to your business if used correctly.

Tracking by classes essentially adds “columns” to your income statement. Taking time to choose the correct classes will help you understand and explain your business while maintaining a shorter and easier-to-read income statement. Appropriately used classes narrate your business to stakeholders and make you look like you completely understand your business, like a boss.